The 2022 Ukraine and Impacted Countries Crisis response faced a complex situation that was changing by the hour. As a result, the operation’s leadership recognized the need to dedicate IM resources towards the development of scenario plans that could help forecast the conflict’s direction and support decision makers with adapting plans as the conditions evolved. This guide walks through how the IM team supporting the operation out of the Budapest office evaluated the situation and developed plans to help make sense of the complexity.

Four paths for the conflict

After assessing what information sources were available and broadly analyzing how military experts were viewing the situation, we developed four possible paths that we recommended the operation be prepared for: de-escalation, stalemate, escalation, and expansion.

De-escalation

A de-escalation scenario looked at what would happen if some sort of lasting ceasefire or peace agreement was reached. Though the Ukraine situation was unique in many ways, there were some comparable historical events that could offer insights into what this would mean. DEEP volunteers were tasked with consolidating information about how the Balkans War repatriation process played out, as well as other recent examples of a conflict ending and the impact it had on people returning to their country. Evidence suggested that depending on the level of resources provided to refugees and internally-displaced people in the place that they moved to, repatriation processes tend to move more slowly than outside observers may expect. The needs, as they relate to RCRC support, tend to shift towards:

- Connecting people with information on safely migrating back, with the hazards they would face in the form of unexploded ordinances, damaged infrastructure, landmines, and other remnants of war being a critical threat to people’s safety.

- Providing shelter support for people whose homes have been destroyed or are no longer safe.

- Restoring people’s livelihoods through a longer-term recovery period.

The IM team had several on-going data collection and visualization processes to support possible impacts to planning that this scenario would cause. That meant developing maps consolidating reports of landmines along key migration routes, tracking markets in western Ukraine where IDPs were pooling, and analyzing what types of skills and trades were in-demand in Europe—the reasoning being that people whose skills would be most desirable in a recovery context may end up staying in other countries if they found stable employment.

Triggers for de-escalation were relatively straightforward to identify; a de-escalation agreement would be a well-publicized event. Tracking the likelihood of such agreements meant carefully following news sources that indicated high-level talks or diplomatic efforts from third parties were gaining momentum.

Stalemate

A stalemate scenario considered an extended conflict where neither side made quick and sustained gains on the battlefield. This meant that while certain towns and cities would be lost or re-gained by Ukrainian forces from week to week, the conditions and needs of the affected population would remain relatively constant and easier to predict. The IM team set up systems for tracking and reporting on border crossings, and provided snapshots that helped stakeholders understand the trends. A stalemate scenario meant that people’s needs centered around:

- Provision of food, water, and medical supplies as they traveled—frequently on foot—from the more militarily active eastern regions to the west and into neighboring countries and beyond.

- Supporting people leaving Ukraine with information to help connect them with government processes for asylum and other resources.

- Cash and voucher assistance to help meet immediate needs.

The IM team operated under this scenario for the entirety of the surge period. This support meant helping decision makers understand people’s needs related to where in Ukraine they were sheltering, and where they were going if they crossed the border into a neighboring country. Support was also provided to CEA teams that were tasked with helping connect people with vital resources, and to the cash team in the form of our standard cash IM technical assistance.

Since we began and ended the planning process operating under the stalemate scenario, triggers dealt specifically with signs that both sides were entrenching themselves in certain positions and preparing to defend certain positions rather than go on the offensive.

Escalation

There was a period in the beginning of the response when it was unclear to what extent Russian forces were prepared for—and capable of—increasing the resources they could or would commit to the conflict. Experts speculated that if it seemed as if Russian forces were being pushed back and the course of the conflict was shifting in Ukraine’s favor, that more dangerous and destructive technologies and tactics could be deployed. This included the possibility of the use of chemical, biological, radiological, or nuclear (CBRN) weapons. This scenario planned for:

- Keeping our staff and volunteers safe, and recommended procuring materials to help protect against the effects of hazards like radiation.

- Facilitating the import of similar protective materials for people within the IFRC’s operational area in western Ukraine.

- How people trapped in eastern regions of Ukraine would either be motivated to try to escape or shelter in place, and what their needs would look like.

The escalation scenario meant working closely with the security delegates whom were tasked with carrying out the logistics of procuring PPE and other materials, and reviewing secondary data and analyses from CBRN and military experts on what the impact would be from various types of attacks.

Triggers related to escalation related to tracking evidence in media and military sources that indicated movement of certain types of weapons and tracking the rhetoric of civilian and military leaders around their willingness to use them.

Expansion

The politics of NATO expansion meant that certain expansion scenarios—those that considered the war expanding beyond just Ukrainian and Russian forces fighting almost exclusively1 inside Ukraine’s borders—were mostly focused on whether Russia was preparing to cross non-NATO borders. The most obvious destination was Moldova, the small country to Ukraine’s southwest, which is not affiliated with NATO and has cultural and historical connections with Russia. An expansion scenario examined what would happen if Russian forces decided to cross into Moldova or other non-NATO countries in the region. The scenario considered:

- Another massive wave of migration from the affected country, and analyzing how the needs of people fleeing it would reflect or be distinct from the needs profiles we had developed for people living in and fleeing from Ukraine.

- How logistics routes that were delivering aid from neighboring countries to the west, including Slovakia, Hungary, and Romania would be affected, along with possible alternatives.

- Where people sheltering in Moldova, as well as Moldovans themselves, would go.

Response plans being developed and used up to this point in the response were dependent on Moldova absorbing and hosting thousands of families. Losing that as a possible destination would have far-reaching implications, particularly for the Romanian Red Cross teams, as they would be most likely to receive the influx of people fleeing Moldova.

Triggers for the expansion scenario focused on two pieces of information: how were Russian forces making gains in the region around Odessa, and what sorts of disinformation and other non-military tactics was the Russian government using directly inside Moldova to shift public perception or weaken its defenses.

Monitoring the situation and adapting plans

After having these possible scenarios documented, we instituted a daily process of information consolidation, analysis, and reporting that centered around the relevant triggers and planning implications.

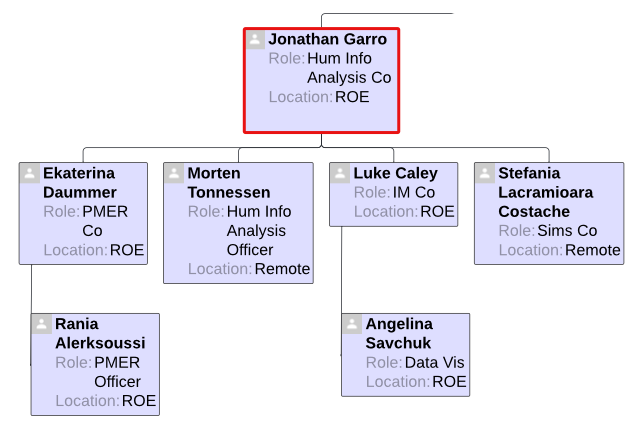

The human resources available to dedicate to a process like this will vary by operation, and that will determine how extensive you will be able to get with your own scenario plans and the work associated with tracking and acting upon them. The Ukraine operation was very well-staffed during the surge phase:

The Humanitarian Information Analysis Officer played a key role in the daily process of reviewing and consolidating information, and processing against the scenarios.

Impact and probability

Two of the most important factors for decision makers within the operation were the expected impact of shifting into a new scenario on the three groups of people that were focused on—people in Ukraine, people on the move within and out of Ukraine, and people that had left the country and reached their destination—and the probability that the situation would shift into that scenario.

Each morning, the IM team led a briefing with the HEOps, the IFRC Regional Director for Europe, and the Head of Regional Health, Disaster, Crises and Climate Unit for Europe. The presentation would review which scenario we were currently operating under, as well what we referred to as “weather vanes”—general indicators of which way we saw the winds blowing in the near and medium term based on the synthesis of available information. Those indicators were designed to provide a best guess, given the available information and expert analysis, as to which direction we saw the situation heading.

Integration of DEEP

DEEP—the Data Entry and Exploration Platform—was an invaluable resource for the scenario plan development and monitoring process. The Humanitarian Information Analysis Officer led regular calls with the remote team of secondary data reviewers in order to help them shift their focus as new elements were added to scenario plans. For instance, if the weather vanes were pointing increasingly to a de-escalation scenario, DEEP volunteers were tasked with focusing on information related to emerging needs of people migrating back into Ukraine so that a more complete profile of migrant needs could be developed. The information would be consolidated in DEEP and then distilled into triggers, analysis of impact, and probabilities.

Documenting and reviewing triggers

Each scenario had a defined set of triggers that served as markers to help us know when we were moving towards a different operating scenario. For example, under the escalation scenario, there were triggers around Russian troop reinforcements, Belarus activity, and mobilization of nuclear forces.

Relevant triggers were discussed daily, and were integrated into daily briefs both for leadership and for the broader operation. These were classified into either “not met”, “partially met”, or “met”. When a sufficient number of triggers were met, that was an indication that we needed to consider changing the official scenario under which we were operating.

Integration of planning implications

A natural question to ask as this process was being developed was “so what?” If we have all of this information, how do we actually help the operation make decisions and plan for possible changes? Sector leads played a key role in bridging this gap between the theoretical and the tangible. We held regular meetings with surge staff that supported health, water and sanitation, shelter, and community engagement and accountability (CEA) to review the latest scenario plans and get their inputs around how the operational strategy would need to change if the situation shifted in one way or another. For example, under a de-escalation scenario where people would start to re-enter the country, we needed to know how the support that CEA was providing to people would shift from connecting them with resources in neighboring countries to connecting with resources for migrating back home.

Conclusion

Scenario planning is a difficult but important part of any operation, but particularly for large-scale responses with highly-dynamic situations. Though IM and PMER teams frequently lead the process, a effective scenario plan requires buy-in from operational leadership and the technical leads. The Ukraine operation’s scenario plans were at the center of many decision making processes thanks to that support. Operations may also lack the requisite human resources to carry out daily monitoring and plan adaptation, which makes SIMS an ideal candidate to support the process.

Footnotes

1: Limited attacks were launched by Ukraine into Russian territory.